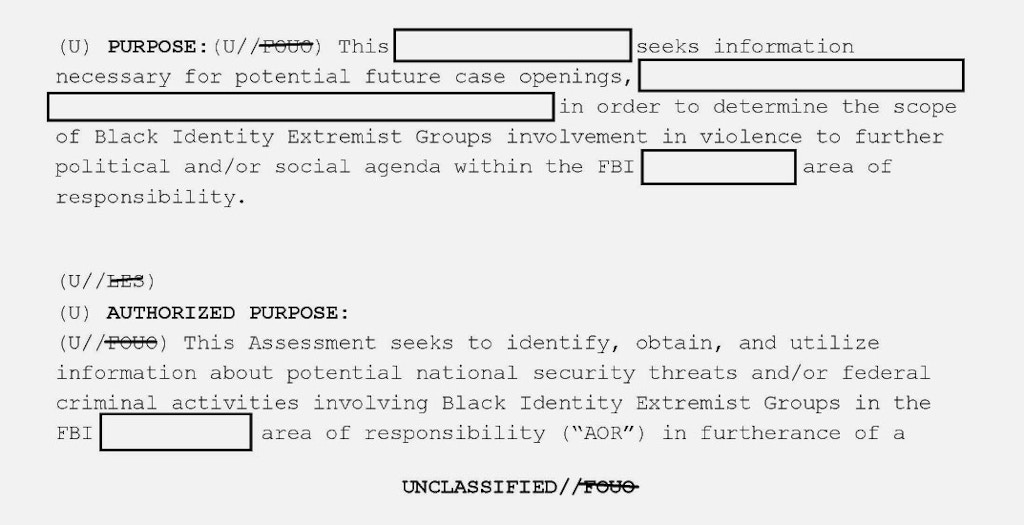

[Book Excerpt #9\”The Roots of Racism in American Policing”]

The murder of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark on December 9, 1969, in Chicago, is an example of outright blatant political police murder.

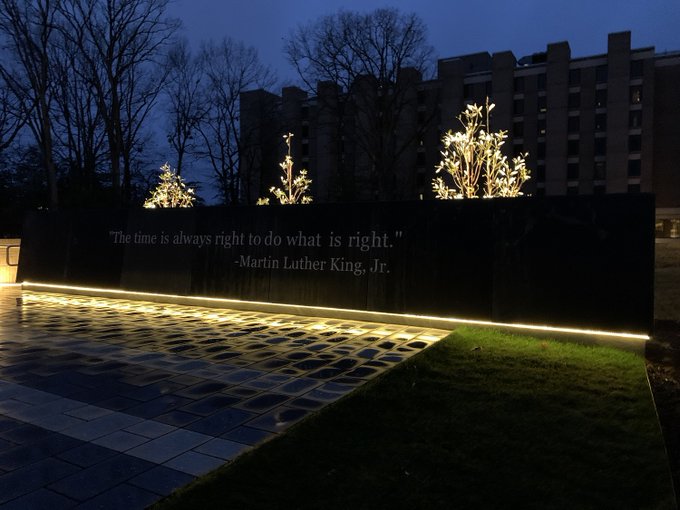

Photo: Facebook

Charismatic Chicago Panther leader Fred Hampton murdered in his sleep by Chicago Police on December 4, 1969.

The following is an excerpt from the upcoming book “The Roots of Racism in American Policing: From Slave Patrols to Stop-and-Frisk.”

Over the last few weeks, the Black Star News has been publishing selected portions from the book. The following excerpt is from Chapter 3.

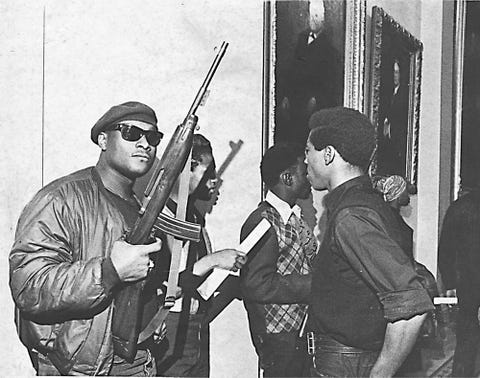

The rise of Black Power groups, in the Sixties, like the Black Panther Party, and later, groups like the Black Liberation Army, were a direct indicator of this rising resistance to police oppression and political white supremacy. The original name of the Black Panther Party was the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. The emphasis on self-defense must not be forgotten since this is a direct reference to resisting the violence and murder of Black Americans by the hands of police. Founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in the incendiary aftermath of the 1965 Watts Rebellion, and the assassination of the militant Muslim minister Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party declared, in point seven of their “Ten-Point Program,” that “We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.”

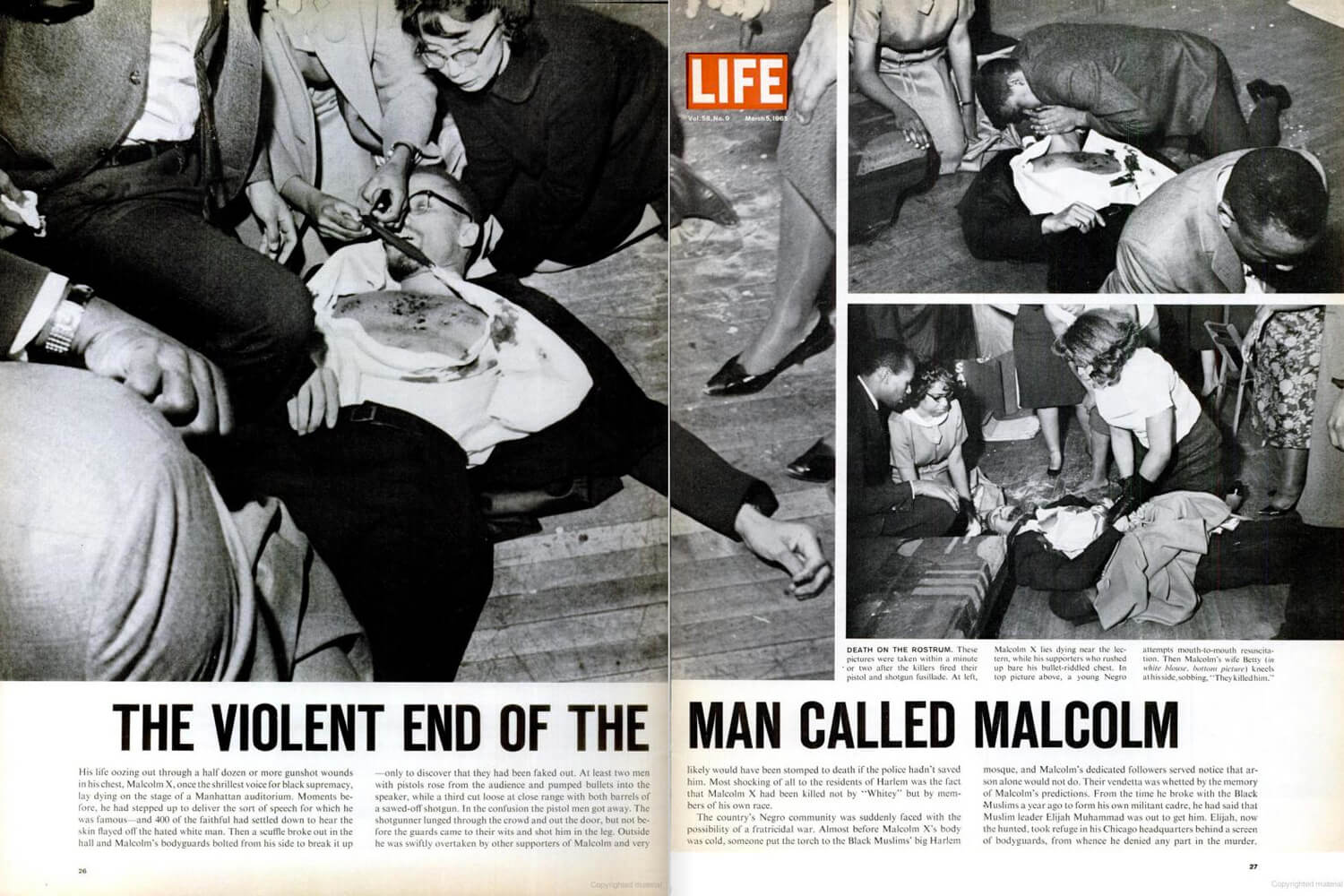

This demand made it clear the Panthers would be on a collision course with America’s white-controlled police forces. Because of their stance, the FBI and American police departments in collusive cooperation embarked on a campaign to destroy and “neutralize” the Panthers, a tactic that would also be used against other Black Liberation groups. This led to some of the most obvious instances of outright police murder of Black radicals and activists and some that are not so clear cut. For example, the latter circumstance seems apparent in the February 21, 1965, assassination of Malcolm X where the NYPD and FBI probably colluded to, at least, create the climate that led to Malcolm’s murder. We now know the NYPD had foreknowledge an attempt on Malcolm’s life would be made that night. Were they also involved? Reportedly, although there wasn’t the usual uniform presence of police at the Audubon Ballroom that day, an undercover police presence was on the scene when the assassination took place. We know that undercover officer Gene Roberts (who had infiltrated Malcolm’s circle gaining access to his security detail) allegedly tried to revive Malcolm. Was he really trying to revive Malcolm or was he making sure Malcolm died? Moreover, why wasn’t Roberts able to stop the assassins–since he should have known about the plot? Was it because he was one?

NYPD elements tipped-off columnist Jimmy Breslin that he should go to the Audubon Ballroom because something significant would occur. This was exposed in the book “The Ganja Godfather: The Untold Story of NYC’s Weed Kingpin,” by Toby Rogers. According to Rogers, after the assassination, Breslin, who worked then for The New York Herald Tribune, wrote a story for the newspaper titled: “Police Rescue Two Suspects.” However, Rogers states that after this initial story ran no further mention was ever made of this other unidentified suspect who is apparently not one of the three people—Talmadge Hayer, Thomas Johnson and Norman Butler—who would eventually be prosecuted for Malcolm’s murder. In 2005, on the 40th anniversary of Malcolm X’s assassination Rogers, who was interviewing Breslin, says he decided to question the legendary journalist on these curious circumstances of intrigue that Breslin witnessed. Rogers claims Breslin started by telling him: “Well I was supposed to receive a journalism award in Syracuse that evening, but I got tip [from the NYPD] that I should go up to Harlem to see Malcolm X speak. I sat way in the back smoking a Pall Mall cigarette.” But Rogers says when he tried to raise the subject of the second suspect and the suspicious omission from The New York Herald Tribune’s coverage, in follow-up and secondary stories about Malcolm’s killing, Breslin’s mood quickly changed. “When I asked Jimmy about the reports of a second suspect and his strange disappearance, both in his Tribune story and the Times piece. All of the sudden Breslin got quite cagey,” Rogers said. “He knew exactly what I was referring to and refused to talk any further.” According to Rogers, Breslin’s response just before the interview ended was: “Fuck it, I don’t want to know no more, that’s it! I don’t fucking know what is what. I don’t know if there was two editions or one. I don’t want to remember. I don’t want to read it. Fuck it. Who cares! It’s 2005, I … fucking dead and disinterested.” Breslin died on March 19, 2017, apparently taking the secrets he knew about Malcolm’s assassination to the grave. All of this evidence strongly suggests that the NYPD operatives who were present at the Audubon Ballroom were likely intricately involved in the plot to murder Malcolm X.

However, the murder of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark on December 4, 1969, in Chicago, is an example of outright blatant political police murder. It was flagrantly done with the blessings of the then Cook County State Attorney’s Office, the Chicago Police Department, and the J. Edgar Hoover FBI. All the relevant facts tell us this.

Hampton, a young charismatic Chicago Panther leader, was executed in a hail of police gunfire—while he slept. Hampton was included on the FBI’s “Agitator Index,” as a “key militant leader.” The essential facts of this case make it clear Hampton’s killing was nothing more than state-sanctioned political murder. The police played their dutiful role by physically silencing this influential Black voice, killing Hampton under the cover of darkness pumping numerous shots into his body as he slept. A Black undercover informer, William O’Neal, was recruited to infiltrate the Chicago Panther chapter, where he became Hampton’s bodyguard. O’Neal drew a layout of the house where Hampton stayed. This act made it easy for the Chicago Police to attack the house and carry out this act of cold-blooded double murder. O’Neal reportedly slipped the drug secobarbital into Hampton’s drink the night before so he would not awaken during the pre-dawn police raid. During this time, and into the Seventies, America’s police departments, across the country, no doubt with the direction of the FBI, carried out numerous assaults—and murdered many Black Panther Party leaders and members.

Today, it would seem obvious to say the current climate between the police and Black America is not quite as volatile. At least, not yet. However, this will probably change if the political powers in Washington continue to turn a blind eye to the brutal institutional racism in police policy that leads to the continued killings and murders of Black people. The Black Lives Matter Movement has made an important contribution towards shining the spotlight on police brutality. For their efforts, they have been vilified and labeled as violent thugs by immoral politicians and police. But while these hypocrites make these sorts of slanderous statements they see it fit to do nothing about the rampant, racist, unchecked, murder that is being perpetrated by police.

In many of the police killings that we’ve witnessed since the chokehold death of Eric Garner and the shooting death of Michael Brown we see police using the “I feared for my life” defense. Even despicable former South Carolina Officer Michael Slager tried to use this excuse for his cold-blooded murder of Walter Scott, on April 4, 2015, in North Charleston, South Carolina. Unfortunately for him, the actions of brave bystander Feidin Santana, who videotaped Slager shooting Scott in the back multiple times, and planting evidence, destroyed his lie. How many police get away with similar acts because no video is available?

In the so-called “land of the free,” freedom was not meant for those who came here as African slaves. And the Slave Patrol police were the main instruments used to enforce this oppression. The police of today are tasked with a similar role as their militia Slave Patrols predecessors: they are the enforcers of a corrupt system that has exploited Black Africans to make America the rich superpower it is today. And their job, especially as it pertains to policing Black America, is very similar to their role during Slavery.